VICTORIA, BRITISH COLUMBIA— Amid the sounds of sticks slamming, whistles blowing, and skates chopping along the frigid ice at the Panorama Recreation Centre in North Saanich, British Columbia—Gregory Simpson dials his parent’s home phone. The Simpson’s ringer flares, disrupting their Thursday evening of puttering and relaxation. Nancy Simpson, Gregory’s mother, answers her son’s late-night call.

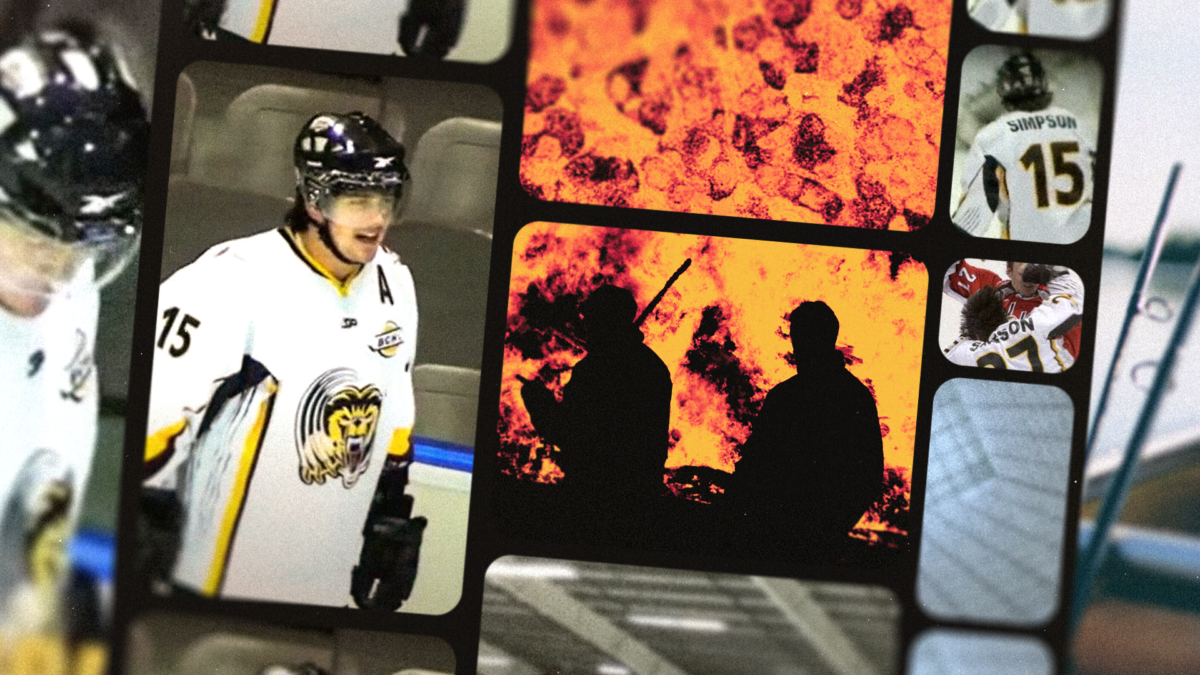

Gregory, a Victoria Grizzlies alumni, now an on-call firefighter, just started his two weeks of vacation. Rather than setting dates for fishing trips with his father or finding time for family bonding, that night—August 18, 2023—he informs his mother he’s catching an afternoon ferry to Vancouver the following day. At 1:00 p.m., Gregory will start a six-plus-hour journey to Kelowna.

“He’s going to the fires,” Nancy Simpson says, turning to her husband Wayne.

A notification popped up on firefighters’ phones in Central Saanich, asking for additional support to battle the McDougall Creek wildfire. Recalling his heartbreaking memories from his experience fighting wildfires two years prior, Gregory knew he had to get out there. Despite being denied to head to the mainland two weeks earlier due to moving up the ladder at the station, he found an opportunity where he’d be allowed to get away. He put his name down, had his two weeks of vacation booked, and awaited a call. Finally, on Thursday night at Panorama Rec, he got the green light. After a few personal calls, Gregory was mentally and physically preparing to leave the next day.

“He kept saying he wanted to go all summer,” Nancy said. “‘I want to get up there. I got to get up there because I can help…I can help.’”

Nancy recalls the smoke, heat, and firefighters who have tragically passed since the Kelowna wildfires broke out—in under 24 hours—her son would be en route to help combat them.

“Just use your instincts,” Nancy Simpson said. “If you need to get out of there, grab that crew and get the hell out… we love you and be careful.”

Gregory promised his Dad a fishing trip before hanging up, giving himself and his parents something to look forward to after the work ahead. Simpson and three colleagues from the Central Saanich Fire Department went to the Swartz Bay ferry terminal the next day. Nerves set in on the hour-and-a-half boat ride—the bunch kept up with the ever-evolving situation devastating local communities in the province’s interior.

Now, on the mainland, the trek to Kelowna brought blue skies with strokes of fluffy white clouds. Lush forest encased the highway. Deer and bear signs scattered every few dozen kilometres, with construction work and unpaved roads lining the streets. The blue skies shifted as the four approached Kelowna. The pungent smell of smoke emerged. Soot and smog filled the light-fallen sky. The low-hanging smoke and vision-limiting conditions spike Gregory’s adrenaline. A ‘business mindset’ is what he calls it once grey and orange began to bleed into the blue skies as they inched closer—quickly, his adrenaline faded.

Gregory and his team set up camp near UBC’s campus in Kelowna, reaching their home base at nightfall, mere miles from the raging fires. Smoke and night skies limit their visibility, blinding them to the surrounding destruction. Among the fiery horizon and draining atmosphere, Gregory’s mental strength and stamina stayed strong, something he’s always been capable of doing.

At 16 years old, Gregory Simpson was diagnosed with cancer.

Hockey became an escape for the hopeful player. A getaway to free his mind from the fatiguing chemotherapy treatments—an excuse to have fun with the guys on his team rather than the realities of his off-ice life—a chance to be an average 16-year-old. His parents noticed a change in him. He wanted to live life to the fullest because, at 16, he didn’t know how long he had.

“Once he had cancer, that changed his life,” Nancy Simpson said. “I kept saying you’re going to be fine… He was playing at the Peninsula Panthers then, and he’d go for chemo Thursday afternoon. Then, right after that, we’d go to the arena. And he would play that night.”

Despite constant puking post-chemo, his parents still looked on from the stands, watching Gregory suit up for the Panthers, the same team he watched his older brother, Michael, play on from the sidelines years prior.

Anyone would understand his want or need to sit on a given night, but he’d still come out to play, play strong, and leave everything on the ice. Simpson brought fisticuffs, facewashes, and ferocious hits, his strength and mental fortitude shining through during the trying time. On the ice, Gregory was a wrecking ball. He’d come out to play with power, grit, determination, and a possessed knack for scoring, qualities foreshadowing his rock em’ sock em’ style with the Grizzlies years later. Every Thursday, Gregory was there to play. Watching behind the glass, Nancy knew hockey was keeping her family together.

“Hockey got us through it,” Nancy Simpson said. “Watching him from the stands, the people there, the coaching staff—the people got us through it. And we did—we got through it.”

After six months of treatment, 16-year-old Gregory Simpson’s cancer went away.

Gregory got into the firefighting business through his brother, Michael. Growing up, Gregory would get excited to watch his big brother take the ice for the Peninsula Panthers. Sat in a red seat next to his parents and sister, the four would watch him play. Gregory idolized Michael. However, their five-year age gap meant Michael often spent more time with his best friend than his wide-eyed little brother. Both were enamoured by hockey—both played Junior B hockey on the Panthers, and both had stints in the BCHL. Gregory became interested in Michael’s firefighting career post-hockey as the two grew closer.

Later in life, Michael asked Gregory if he wanted to join. Gregory applied to volunteer, following in his sibling’s footsteps. He reapplied two years to another recruiting class after his initial attempt, this time proving successful. Years ago, as a volunteer, with his sibling on-call, Gregory would look to have sleepovers with his big brother.

“Gregory would mention he’s going for a sleepover at the fire hall,” Nancy Simpson said. “They work well together… he would sign his name off because he tried having ‘sleepovers’ with his brother.”

Their parents paint the two as a silent, stoic duo, sharing similar hobbies like fishing, hunting, and hockey; given their tight bond, it’s easy to assume they talked for hours during their nights at the fire hall.

“It’s always just been a joy working with him,” Gregory Simpson said. “We’ve been around each other more now that we’ve got older. We were never that close when we were younger, but now, being firefighters together, we’ve got a lot closer.”

The timing didn’t align for Michael, currently the captain of the Central Saanich Fire Department, to join the team from Central Saanich battling in Kelowna, but the team stood firm. Discussions of flickering confidence never arose. Entering a foreign subdivision none of the four was familiar with, the firefighters truly understood the impact of the wildfires. Fire loomed on the hillside. Heavy smoke encompassed the campus as the team set out to stifle hot spots and protect houses in Upper Canyon and surrounding communities—a sunset orange cast over Simpson. The ash-filled sky inhibited the sun from peaking through the hoards of thick smoke filling the air during the daytime.

“It smelt like a big campfire all day.” Gregory Simpson said.

The fires sometimes came within 10 feet of Simpson. The heat, more potent in their wildland gear than their structural gear, tested their limits. While the four were typically stationed in the countryside, the smoky conditions would limit their visibility to a mere five feet while protecting houses.

Residents’ doorbell webcams caught the quartet, their parked truck, and other fire stations fighting the blazes in various subdivisions. Residents called Simpson’s station from towns far away to thank him and his crew. One couple brought freshly baked cookies and popped into the fire hall in person. They hugged their heroes, looking at the crew fighting to keep their homes safe. Simpson donned the pump operating role in most instances. He’d communicate via radio to his crewmates despite their often close proximity to one another.

On a different day, Simpson responded to a radio call from an agency requesting assistance. A fire was coming up on a house—at the time, the Central Saanich team was checking for hot spots around the neighbourhood. They roared down the hill, adrenaline surging with the fire coming into their direct line of sight.

“You just kinda go to work and not really think of what’s around you,” Simpson said. “Just put your mind down and be aware of everything. We put the fire out, and that was it—you just do it.”

Similar to his initial approach as they entered Kelowna on the ride up, Simpson’s business mindset set in, allowing him and his team to put out the blazes encroaching on people’s houses.

At the age of 17, Gregory’s cancer came back. At the time, the Simpsons were already dealing with so much.

“We had lost Wayne’s dad when he was diagnosed with cancer,” said Nancy Simpson. “We had lost our nephew, Steven, on the Pat Bay highway when he was 20, and then Gregory got struck with cancer. It was just… boom, boom, boom, how much more can we take?”

Simpson needed a stem cell transplant. Neither sibling was a match, and he had to go to Vancouver for care. The night before his admittance, he went in for a checkup—the doctors did their tests. As Simpson rested on the hospital bed, awaiting the green light to proceed with the treatment, 17-year-old Gregory was handed forms.

“When I was laying there, I had to sign a piece of paper that if I die over there, they can’t take responsibility,” Gregory said. “That’s when I really knew it was real, and things must be changed. I am sick. And if I don’t get better, the alternative is that I won’t be here.”

He signed off, allowing the weight of the situation to set on his young shoulders, but Gregory was determined to return to good health and hit the ice again. Given a rough outline of a past patient’s timeline, Simpson aimed to beat the 20 days of the former patient’s recovery.

They placed Gregory in the adult ward—in retrospect, a decision his parents look back on fondly, preventing them from seeing the suffering of other little ones in similar positions to their son. Soft green paint coated the crystal-clean walls of his assigned room. The bitter, antiseptic odour filled his nostrils, containing slight undertones of an artificial cleaner that permeated inside his hospital room. Thin blue pillows with a stiff, light comforter are where he’d sleep. The poignant smell, dull walls, and machinery lining the room became Gregory’s personal jail cell, cooped up for the week’s head in hopes of getting better.

He suffered the worst in his first two weeks at Vancouver General Hospital. Gregory’s situation was severe, drained from intense chemotherapy sessions before his transplant. His weight dropped drastically. Despite the doctor’s reassurance, Nancy felt empty watching her son struggle.

“You’re crying inside,” Nancy Simpson said. “He kept saying he just wanted to go home; it was tough. But at the very end, he just rallied.”

The doctors used Gregory’s own stem cells. His body reacted to them well, his blood count returning to good health in the following days.

“They used his own stem cells—they cleaned them up and used them,” Wayne Simpson said. “He was very sick. Within two days [following the stem cell treatment], he was back to normal health. He reacted that fast with his own stem cells. The Doctor said they locked together, and boom, his blood count went right up, and he was right back to normal, if not stronger.”

“He was able to donate his stem cells too, for anybody that needed it in the future,” Nancy tacked on.

The end was near. Soon, he’d be free of his confined room, the stale hospital smell, and the IVs sticking in his arm.

Four weeks following his admission, Simpson was admitted to outpatient care. The hospital staff monitored his vitals, ensuring his blood levels stayed consistent. In his last appointment, the doctors informed Simpson he’d go home with monthly bloodwork checks. At last, for Simpson and his family, greener pastures seemed to be coming.

“It wasn’t just me going through treatment,” Simpson said. “Just watching your parents suffer, watching their kid go through all these treatments, it’s quite an emotional ride.”

After five weeks of intense care, Gregory was officially clear of cancer. Doctors and nurses watched as he made his way to the exit of Vancouver General Hospital. Applause broke out. The staff clapped and commended his resilience, telling him to get out there and enjoy life to the fullest. Officially discharged, Gregory went past the sliding doors. Sunlight kissed his skin for the first time in weeks. Finally, outside, he looked ahead and took off running.

Gregory ran and ran and ran. His parents called after him. Worried for him in his frail state after his lengthy battle with cancer, urging him to stop… but he ignored them. Simpson ran with all he had, rifling towards the water sitting blocks away from the Vancouver General Hospital doors.

He breathed in fresh air for the first time in weeks. His running broke through the still weather falling on that Friday. A cool breeze glided off his skin as he reached the ocean. He soaked in the scents of saltwater and seaweed, listening to the occasional chorus of seagulls squawking from the sky above.

“After being cooped up in a hospital for weeks, you know you can leave, but you can’t because you’re trying to get better,” Simpson said. “The relief of the fresh air and the smell is just… emotions came over me. I just ran and smiled.”

After two miles, he stopped. Following five weeks of treatment, Gregory was free. Free from the soft green jail cell where doctors nursed him back to health. Free to train for the upcoming Victoria Grizzlies tryouts and return stronger than before. And free from the cancer trying to steal the 17-year-old’s childhood.

Simpson spent nearly a week battling the fires. On his last day, he finally saw blue skies peeking through the smoke as they began their journey back to Vancouver Island. The McDougall Creek fire raged on, but Simpson found solace knowing he helped a community in need, hopefully saving a few houses among the losses.

Simpson and his crew made it home safely. Their families burst with pride seeing, in their eyes, real-life heroes come home after tirelessly helping a community in need. However, Simpson sees it a little differently.

“I don’t see myself as a hero by any means,” Simpson said. “There are many people out there who probably were heroes. We’re just a small little piece—four guys from Central Saanich trying to help out a community.”

The four guys showed poise and mental toughness. Simpson, whose childhood shaped him into the man he is today, played a role in his ability to stay calm while staring down the barrel of danger.

“Sometimes you have a strong mind to carry on; you can’t let things overcome you,” Simpson said. “In firefighting, you see some things nobody ever wants to see, and being mentally strong from going through treatments as a kid, I think it’s pivotal where mental health is a major issue in firefighting and life in general. From that standpoint, all those years of treatment made me mentally strong. I know when to step back and say no when I need a break…Going through that as a kid helped me become mentally strong, but it was humbling at the same time. You view everything with a different outlook now—where life is so fragile—where you see things and show compassion.”

Simpson reached Victoria Thursday night, one week following his flurry of calls to family and friends letting them know he’d be heading to fires. The next morning, he fulfilled his promise to his father.

Gregory, Wayne, and George, an 84-year-old family friend, went fishing off the Victoria Waterfront. They arrived at daybreak. Mellow, orange rays appeared over the horizon, illuminating the dim sky. The flat bed of water welcomed the three with promises of fish for those with the mental fortitude to wait. The three caught their fair share and reached Tim Hortons by seven a.m., ending their short and sweet excursion on a high note.

Happy with their haul of fish, Gregory, one of the best filleters in the family, turned to George with a smile beaming across his face and joked.

“Hey, old-timer, maybe I can give you a few lessons when you’re ready for it.”